These are the chronicles of the esoteric . . .

From 'The Crucifixion,'

by Matthias Grunewald (1515)

Matthew 26:17 tells us it was the first day of the Festival of Unleavened Bread when the disciples inquired of Jesus as to where they should prepare for the Pesach Seder - the Passover meal proper; both Luke 22:7 and Mark 14:12 corroborate this timing. Traditionally, on the Day of Preparation chametz (leaven) is completely purged from the household, and this is likely what the disciples were implying was necessary to do in order to prepare for the meal. Differing interpretations of tradition based upon Exodus 12:18NRSV.

In the first month, from the evening of the fourteenth day until the evening of the twenty-first day, you shall eat unleavened bread. make it somewhat difficult to pinpoint the date; by the time of the first century, many Jewish families ceremonially burned chametz, but did so on different days and different times of days depending on how the passage in Exodus was read.1 Because the Gospels are quite explicitly unanimous with regards to the day of Jesus' crucifixion being on the Day of Preparation,2 it is not implausible that the above exchange was late Nisan 13/early Nisan 14 - which would then be consistent with being the first day of the Festival of Unleavened Bread.

What this also implies is that the Last Supper we read Jesus partaking of with His disciples was not the Passover Seder - or at least not a traditional one, which would have been eaten, depending on your Jewish group, either at the end of Nisan 14 or the end of Nisan 15. Because Jesus died during the day it would be impossible for Him to eat at the traditional hour that evening or the next. This notion is one that many scholars are beginning to suggest in light of new research, albeit not without opposition. Still, verses such as John 13:1-4NRSV.

Now before the festival of the Passover, Jesus knew that his hour had come to depart from this world and go to the Father. Having loved his own who were in the world, he loved them to the end. The devil had already put it into the heart of Judas son of Simon Iscariot to betray him. And during the supper Jesus, knowing that the Father had given all things into his hands, and that he had come from God and was going to God, got up from the table, took off his outer robe, and tied a towel around himself. support the argument that the supper Jesus ate was before the feast of the Passover. Moreover, many scholars make the argument that in Luke 22:15 Jesus, in saying He will not eat the Passover until it is fulfilled in the kingdom of God, is in fact saying He is not going to eat it because He's going to be dead when it actually comes time to enjoy the Seder.

Tyndale House of Cambridge, UK, published a paper in 1992 in which the authors attempted to ascertain a precise date of Jesus' crucifixion using astronomical data that coincided with the biblical accounts. Taking into consideration that the Gospels agree Jesus died on a Friday in addition to considering the years in which a lunar eclipse occurred3 as well as the political arrangements of the time - and eliminating Nisan 15 as a possibility due to its occurence on a Friday being too early (27 CE) or too late (34 CE) - they concluded that Jesus was likely crucified on 3 April 33 CE, Nisan 14.

So what does all of this matter? What does it mean in the end? What is the big deal with Nisan 14? Well, I'll let Paul explain: Clean out the old yeast so that you may be a new batch, as you really are unleavened. For our Passover, Christ, has been sacrificed (1 Corinthians 5:7, emphasis added).

According to Exodus 12:6, the unblemished lamb is to be slaughtered 'between the evenings' as part of the Day of Preparation readying. While the Hebrew is somewhat ambiguous, by the time of the first century, 'between the evenings' had come to be understood as during the afternoon of Nisan 14. That is, the lamb was to be slaughtered sometime between our 2PM and 6PM. If we look at the Gospels, Jesus was crucified at noon and died at 3PM;4 thus, He died during the time of the afternoon the paschal lambs were being sacrificed.

Jesus' forerunner, John, did not hesitate to immediately name Jesus 'the lamb of God' - twice! - pointing towards this very fact we've been examining.5 So what is the significance? How should this inform our atonement theologies? Such themes will be examined in the conclusory post next time.

1. The more orthodox Jews of the time kept the Passover meal on the night of Nisan 14 with the Festival of Unleavened Bread beginning the following day, on Nisan 15, as Exodus as well as Numbers 28:16-17 and Leviticus 23:5-6 seem to imply. However, many began to lump together the two festivals (Passover and Unleavened Bread) into one on the night of Nisan 15 - which is often what occurs in our contemporary age. Futhermore, many Jews believed that because unleavened bread was to be eaten during the Passover that chametz was to be purged earlier than the meal of Nisan 14, some doing so already on Nisan 13.

2. Matthew 27:59-64; Mark 15:42-43; Luke 23:50-55; John 19:14-16, 31, 41-42.

3. Some scholars believe Peter's quoting of Joel in Acts 2:14-21 indicates that the reference to a lunar eclipse ('moon [turned] to blood') was a fulfilment of prophesy which occurred at the crucifixion.

4. Matthew 27:45; Mark 15:33; Luke 23:44.

5. John 1:29, 36.

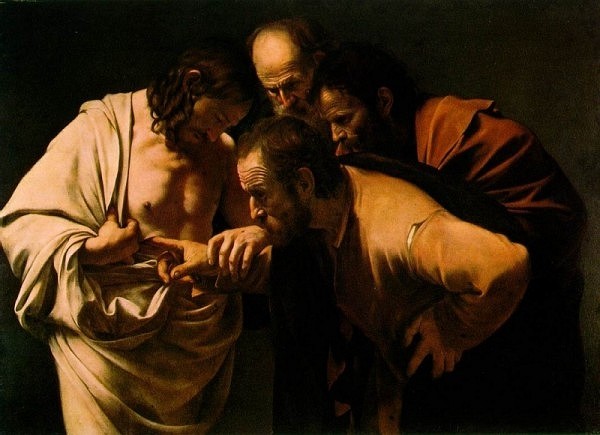

'Doubting Thomas,' by Caravaggio (1602)

Driving to work, one car among many, my mind couldn't help but move towards the apostles and what that first day, that first week would have looked like following the day they witnessed their master resurrected from the dead. The day prior, the apostles' lives were turned upside down as they watched Jesus die on the cross; they hid behind closed doors, dejected and hopeless. But then, at the beginning of the week, their lives were flipped over once again but in a wholly different way as they moved back into the world renewed with the knowledge that Jesus did not remain entombed. They were no longer defeated - nay, exactly the opposite.

Jesus' resurrection changed everything for the first disciples. But our modern minds don't fully understand why. We're aware of the physical aspects surrounding Jesus' crucifixion - as well as, for the most part, all the political scheming. Yet, aside from the obvious fact that their beloved rabbi was executed and then raised from the dead, what was the significance of the event for the apostles? And why is Jesus' death and resurrection so important for all disciples throughout the ages? What did it mean that God hung nailed to a cross as a human male and then was brought back to life?

These are questions hotly debated by believers throughout every century since it happened; as a result, there were three major models that developed to give some level of understanding - to grope for the divine - thereby facilitating discussion about the event and its significance - the atonement - with a common language.

-

Christus Victor

This model came into popularity largely during and after the reign of Constantine in the fourth century, as Jesus increasingly became depicted in parallel fashion to the emperor (and as a result, became theologically distanced from His followers, perceived more like a high and lofty king than a personable teacher), but was around as early as the second century. This model states that when Jesus died He defeated the power of death and thereby freed every human from the hold of the devil. Thus, Jesus gained the greatest victory. -

Christ as Ransom

This particular theory, which arose in the twelfth century from the reflections of Anselm, posits the idea that Jesus died in the place of each one of us - we were all deserving of the punishment Jesus endured because of our sin, but He went through it for us, instead of us. Taking our iniquities, He paid the price we were unable to, therefore the punishment due to us because of our sinfulness has been satisfied. -

Christ as Moral Example

Jesus' entire life and ministry are taken into account by this model, putting them forward as the examples for us of how to live our lives in complete union with Adonai. It is only by shaping our lives after Jesus' that we can obtain salvation, and doing so inevitably leads to a collision with the world and its powers, possibly ending in death (martyrdom). The foremost proponent of this theory was Abelard, a contemporary of Anselm, and he strongly argued that Jesus' atoning work was complete only when, by faith, it was appropriated and thereby allowed to transform one's life.

Pesach (or, as we know it, Passover) is not only the most important of all the biblical festivals, but also the first, and it was at this exact time of year Jesus' earthen ministry came to a head. Not coincidentally, many rabbis believed that the Messiah would appear at the time of Passover, and it is, I believe, through this lens alone we can come to an understanding of Jesus' crucifixion and resurrection.

1. Historically, many have taken uncompromising stances in one of the theories, declaring that particular theory as the only and exclusive truth to the atonement. Even today such polarised battles rage, but this is an inappropriate view to take on these models; each of them have something to bring, as well as something to be cautious about.

2. This fact easily answers the question Sunday School never seemed able to of Jesus' whereabouts before he began his ministry: as a good first-born male Jew, he would've been devotedly studying Torah - surely surprising his teachers with his knowledge like he did as a 12-year old child - thus earning the right to be called 'rabbi.'

In Spring none of the dualistic qualities of December seem to exist. The overarching impressions are those of chocolate, bunnies - chocolate bunnies! - as well as painted eggs and long weekends. For Easter, unlike Christmas, the original pagan themes and images seem to endure prominently and overwhelmingly. While at Christmas there is somewhat of a coexistence of both Christmas and the Holidays, at Lent there appears only the festival of Eostre - the goddess of fertility worshipped by pagans in spring - and its images. First century Christians largely employed the symbols of a shepherd carrying a lamb on its shoulders, as well as a fish (often two, in fact). Additional symbols found among early Christian catacombs were palm leaves, peacocks, a dove, an anchor, bread and chalices of wine (or a bundle of grapes); it was not until the empire under Constantine in the fourth century that the cross became a popular representation of the faith. Today it is essentially the only symbol of Christianity used, oft-times bejeweled and gilded - easily digestabe. Yet at this time of year it is scarce at best.

This time of year is supposed to be vitally important for us as Jesus-followers, but what Christian themes arise and which Christian images persist? In what way do we distinguish these holy days from not only the rest of our calendar, but also from the rest of the world's Eostre celebrations?

Lent is a sombre season, observing and commemorating the life of God as a man, which culminated in His death and resurrection. It is a time of introspection and as a result has become, in some ways, privatised. Further, the church seems to be afraid to boast in this, despite its unabashed zeal for proclaiming the Christ-baby in December.

But this makes sense: Lent has a hard message. When we seriously think about what we're observing, we ourselves may even be taken aback. Do we, as believers, fully understand what's going on?

We know the overall details of Jesus' last days. We know the anxiety, the celebratory meal where Jesus outright reveals His betrayal. We know the torture, and we know the murder. But verses such as Matthew 27:28-30NRSV.

They stripped him and put a scarlet robe on him, and after twisting some thorns into a crown, they put it on his head. They put a reed in his right hand and knelt before him and mocked him, saying, 'Hail, King of the Jews!'. only give hint of the actual humiliation Jesus underwent; moreover, the mentioning of the twisted crown set on His head doesn't describe the pain of thorns gouging their way into His scalp. Verses such as Mark 15:15NRSV.

So Pilate, wishing to satisfy the crowd, released Barabbas for them; and after flogging Jesus, he handed him over to be crucified. seem to gloss over Jesus' flogging, neglecting to inform our modern minds of the intentional design to the whip used by the Roman floggers so that it tore at flesh, exposing muscle and in many cases bone. The fact that Simon of Cyrene was forced to carry the crossbeam of Jesus' cross1 - the patibulum which weighed around 70 lbs - merely implies of Jesus' inability to do it Himself, leaving out the fact Jesus' inability was due to complete and utter exhaustion, not to mention the amount of pain He was then experiencing coupled with massive blood loss.

The Romans had killing down to an art. The crucifixion was engineered particularly for a long and agonising death. When Jesus was nailed to the patibulum and raised to rest on the post dug deep into the ground, it was only the beginning. There was a reason why, at the time, the cross was viewed with great aversion. The victim, following somewhat of a lesser torture than Jesus endured,2 hung on the cross for days experiencing shock and dehydration, tied with a rope around the traumatised thorax so as to keep the body from ripping away from the nails. Unlike our pictures of towering crosses, however, the scene was much more taunting: the victim only hung a few feet from the ground, teasingly. As the torso's muscles failed, the crucified slowly asphyxiated.

Jesus hung nailed for an afternoon, losing blood, withstanding excruciating pain, until he finally gave up His spirit. Where the victim's legs were broken to ensure the drop of the body, ending their torture with finality, Jesus was already dead. He hung there, lifeless.

And this was His fate. He knew it. He chose it, albeit anxiously. Yes, Jesus of Nazareth, Adonai's Anointed One, gave Himself to this.

It is these grim and grisly details we push aside in favour of brightly coloured eggs and chocolate animals. Such so-called 'Christianised' pagan traditions only serve to usurp the real reason we observe Lent, unnecessarily lightening the mood and adding extraneous rituals. We're so unafraid to herald the God-baby in a manger, yet the miserable cross is hidden. Eggs and bunnies dilute the seriousness of death, cheapening the sacrifice of Messiah Jesus, Elohim's chosen son.

And isn't it this we are proclaiming in these final days of Lent - that Messiah Jesus willingly died to reconcile us to His Father, Elohaynu? But where do we see that in our Easter celebrations? Where is the bloodied cross and piercing nails? Where is the torn divine-flesh? Where is the martyr of salvation?

1. Matthew 27:32; Mark 15:21; Luke 23:26.

2. I say 'somewhat lesser' simply because Jesus was also beaten and mocked by the Jewish authorities prior to being handed over to the Romans. The rest of the torture would have been more-or-less the same for any criminal.

Comments (0)

Comments (0) Contact me!

Contact me! See me on Facebook!

See me on Facebook!